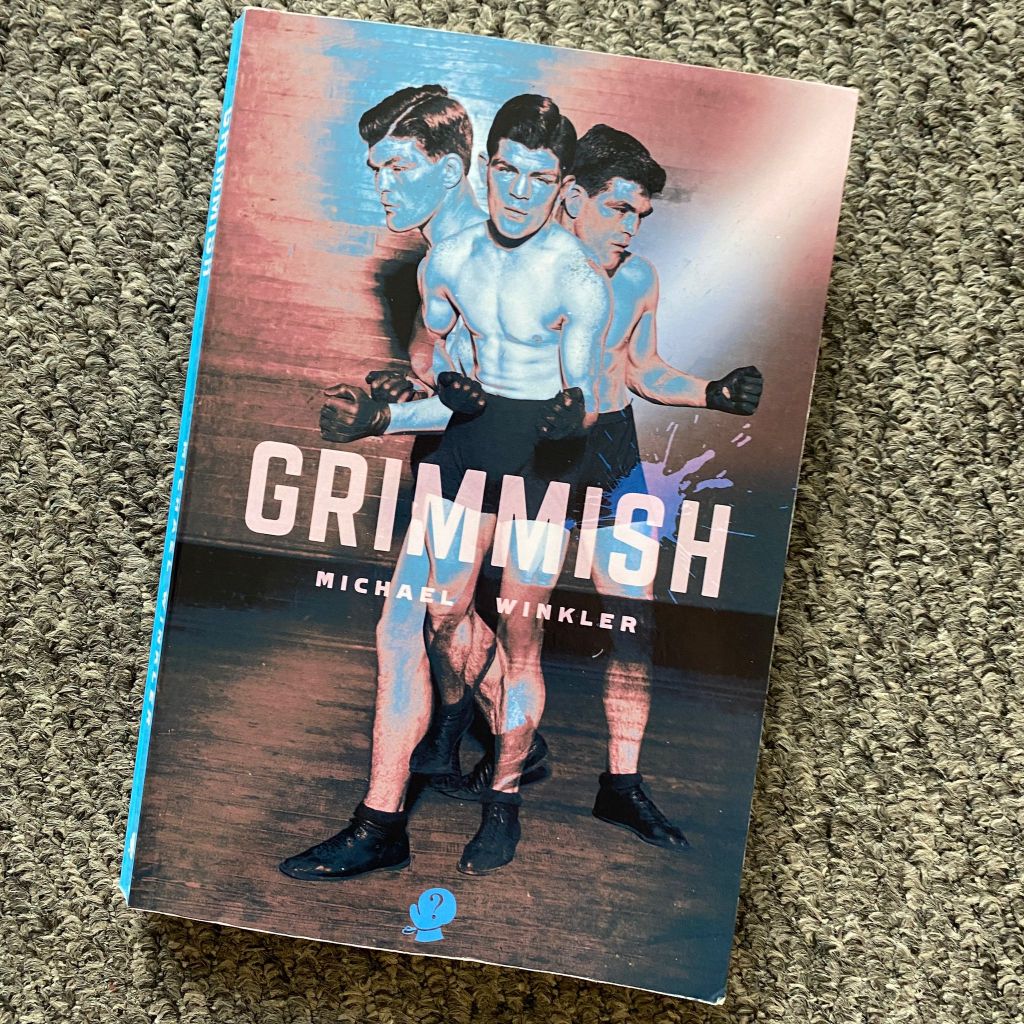

‘Grimmish’ is Michael Winkler’s exploded non-fiction novel about Italian-American boxer Joe Grim’s time in Australia. Published in the UK by Peninsula Press and in the US by Coach House Press.

Note: This post differs quite widely from the others on this blog. This is due to the nature of the book and my own response to Michael Winkler’s writing. Please do remember throughout that this is very much a book about a boxer who conducted his life as a professional, and my ramblings about writing shouldn’t put you off buying it 🙂

Ah gahd!! Wot a book!!! I’ll do my best here to explain why and how much I love this book, but I’m already doubting my chances to do it justice.

This is the only book which I’ve gone back to in order to re-read before writing about it. Firstly, it’s such a deeply layered book, in terms of both form and style; secondly, as a book of any genre, this has made me consider the way I think about writing most, since reading Lydia Davis and the translated novels of Linda Boström Knausgård. I couldn’t trust my memory enough to commit my thoughts to this website, even after just a few months of reading the book originally.

Ironically, the winding narrative through ‘Grimmish’ explores what it means to remember something… anything… with the passing of time, and with the bias of one’s own emotions. The story is told to the book’s version of the author Michael Winkler, by a man who may or may not be his uncle, and who may or may not be real: ‘Uncle Mike’. Uncle Mike tells us about how he came to know and befriend Grim during his 1908-09 travels across the continent of Australia. Uncle Mike tells his story from ‘first-hand’ accounts, and newspaper clippings full of the usual casual racism and xenophobia that was fairly standard at the time. A period in which there was still a colour bar for world championship titles.

(Grim’s time in Australia is also important as it overlaps with Jack Johnson travelling to the continent in order to fight Tommy Burns for the world heavyweight title. Joe Grim was said to have sparred both men.)

Incidentally, I don’t know if I’ve just been reading too many books about boxing in the early 20th Century, but is it just a coincidence that there is an ‘Uncle Mike’ acting as oracle in this book? It’s a (nick)name shared by Mike Jacobs who, a couple of decades after Grim’s retirement, would go on to control and define the narrative around just about every world title bout for a considerable time, in his capacity as Madison Square Garden matchmaker.

Whether I, or we, or Uncle Mike truly remember anything becomes irrelevant throughout this book, as it is more an exploration of what it is for someone(‘s story) to become myth and legend. Grim’s whole legacy is so utterly ridiculous, and it happened at a time of such heavily biased views of him as an Italian and a prizefighter, that searching for any version of the truth seems a pointless task. The book instead focuses on trying to examine why we have the version of Grim in our collective mind that we do.

And found: singular, astounding Joe Grim, more forgotten than remembered.

As well as memory, the book examines what it means to experience and to inflict pain. For those who are unaware, Joe Grim went by the nicknames Iron Jaw and The Human Punching Bag, due to his unbelievable punch resilience. I say unbelievable deliberately, as I still cannot believe that he faced some of the fiercest fighters and punchers of his time and not only was he not stopped in any contests, but he wasn’t killed in the ring. Of course, whether I believe it or not is irrelevant.

A whisper of a whisper of a whisper.

His legend exists completely outside of my ability to conceive of it. Boxrec has Grim’s career listed at 179 bouts, of which he lost the vast majority, not only losing but getting soundly bashed up.

No man ever tackled world champions across three weight divisions in four straight fights, and no-one will again.

The book asks the important question: what is pain? Is it something that we can all learn to endure? Most of us probably already carry a deep pain that we endure, and the drive we have to continue regardless is something we probably can’t or don’t have the desire to examine. Is pain something that Grim experienced but was able to overcome? Did Grim ‘simply’ have an extraordinarily high threshold for physical pain, or did he, for some reason, not experience it in the same way as the rest of us?

Where does any pain in the world end up?

A question often overlooked but tackled in this book is: what of Grim’s opponents? What did they go through when beating Grim (in front of a crowd (for money))? What did it do to their ego, seeing this man bounce back up after absorbing their best shots, shots that would have left even the the strongest heavyweights of that, or any, period incapacitated?

…this infernal man who couldn’t win but wouldn’t be beaten, at least in terms of the contest as he constructed it.

How did they deal with the embarrassment of so publicly losing side bets, by not being able to stop Grim? How did they find the motivation to keep punching, in the head, a man who would simply smile back while often being unable to return fire? How do you beat a man that is simultaneously beaten and refusing to lie down?

What must it have been like to strike at Grim with all of your force, to see a man disarmed of any conventional boxing defence, and yet unable to stop him standing in front of you? Sinking your fist up to the wrist into his midriff; clattering blows off his skull until your knuckles snapped – but he would not be denied.

There are interesting reflections in the book as to why crowds were so drawn to seeing Grim being beaten so thoroughly. Were they hoping to see him killed in the ring? Were they living vicariously through Grim, who was giving them some hope that they too would continue to bounce back up after being knocked on their arse by The Big Man? Viewing Grim’s career through a modern lens, in a time in which he would surely had his boxing licence revoked by every governing body in the world, fails to acknowledge how far away we are now (and how close early 1900s audiences were) to any form of gladiatorial combat, in which there was an honour in absorbing extreme amounts of pain in pursuit of immortality, either in the memories (here we go again) of those present, or anyone they pass their stories on to.

I have to say, Your Body is like a Laboratory, it is amazing, you are a Scientific Instrument for measuring pain.

This brings me to the religious aspects in the book: now, I grew up in a household with a mum who had had terrible experiences with nuns in a south London Catholic school and it was a place of little or no religious talk, so I’m probably lacking the required knowledge to be able to expand much on this theme, but… It feels as though Winkler is pushing the reader toward considering that, had Grim been born at a different time, when his profession wasn’t looked down upon in quite the same way, he would have been sanctified.

What little Catholic memory that does exist in me contains a heavy emphasis on people who had supposedly been through huge suffering for a singular belief. Often a belief placed upon them by others. On that note, throughout the book there are characters wandering through deserts, refusing temptation, washing feet, enduring terrible mental and physical and emotional pain, beasts of burden…

This brings me on to the talking goat! It’s important to mention this as, well, it’s just that kind of book. You should probably know what to expect! As a writer of what some would call innovative or experimental work, and a person whose life is submerged in reading and thinking about boxing, there’s a bit of a running joke amongst friends that now I have ‘Grimmish’ in my life, a book so ‘odd’ in form, centring around a boxer whose life story may be mostly fiction or hearsay, and with one of the central narrators a talking goat, I might never need to read another book again! I’ve probably ‘completed’ reading now.

Throughout, the author wrestles with the notion of writing for his own pleasure. Striding forward with a book which no doubt felt like it would be alienating more and more readers, the closer it stayed to its original ideal. Important questions about who writers should be writing for, and how the success of a particular project should be gauged, are asked. Importantly though, what does it mean to deliberately write a book that so obstinately sits outwith standard genres? Is this just a way of producing work that can’t be compared to the canon, and can therefore never really be considered to have failed because it was only ever an experiment?

I had a poetry collection published once (Contained), which ‘explored’ form and style, and I do honestly believe that, at the time, I wanted to experiment with what a book could be; but as time has passed, doubts have crept into my mind suggesting that it was all some sort of folly, and an act of self-protection/sabotage which meant that, by deliberately not engaging with the poetry trends and styles of the time, I could not be told I had been an abject failure at something I put perhaps too much energy into.

Sure. You can style the ongoing embarrassment of your unexceptional career as a glorious refusal to conform to audience dictates, performatively embodying the stubborn idealist who chooses what others want to read. Thus I am not an abject failure as a writer: no, I am triumphing in my own contest on my own terms. And it makes me about as happy as it made Grim, although less wealthy.

I identified, strongly, with the version of the first-person author that exists in this book, as he struggled under the weight of words already written. Often sitting on banks and mountainsides of books, newspapers and journals. A nice analogy for the weight of responsibility in attempting to write about the earliest professional boxers, who often had hundreds of bouts. How do you do justice to that sort of career?

I’ve never written anything that has required the kind of research which is no doubt involved in writing a book like ‘Grimmish’, but I did produce a fairly long-running podcast series in which I interviewed poets about their work and influences. Toward the end of my time as its producer I felt, acutely, the weight of responsibility to try to somehow represent as many voices as possible, past and present; and it often felt like trying to scramble up a sand dune with the grains of sand giving way under my fingers. I eventually turned it into an impossible task. I really should have tried to enjoy myself.

We are not always proud of the things that obsess us.

The book features a lot of footnotes, something a lot of writers use when experimenting with form. This is something I’ve not done much of, probably because I don’t have an academic background, and I’ve only recently begun searching for and reading theses and academic papers. The footnotes give a constant reminder of the research needed to form a picture of a historical character, but also, as someone who came to classical literature relatively late in life, it allows me to feel like I’ve engaged with some heavy thinking, by virtue of having read so many quotes in the book. I also get the impression that this is slightly tongue-in-cheek by Winkler, maybe aping classically dense and heavy academic writing.

There is a thing called courtesy: that can mean doing the reading and finding out the accepted wisdom before opening your mouth and styling yourself as wide-eyed truth seeker when in fact you are just too lazy to ascertain what better thinkers have postulated.

This aspect of the book reminded me of conversations I had with my good friend and poet Nils Christian Moe Repstad about writing, but specifically the reading he felt necessary in order to write. Nils is one of the most widely-read people I’ve ever met, and his list of required reading was, and is, frankly bewildering. Often I could do nothing but laugh when I imagined trying to find the time to even attempt to catch up on his list, even if I had wanted to. It was though always fascinating to reflect on how different our approaches were, to effectively trying to write short pieces of prose that very few people would ever engage with.

Toward the end of the book Winkler delves into what society thought about Grim’s mental wellbeing. On 2 July 1909, Joe Grim was committed to the Claremont Asylum, after what seems like a fairly strong psychotic episode. As someone who has also spent time in psychiatric institutions, coincidentally for reasons surrounding my own methods of dealing with pain, I had to read these sections whilst negotiating my own surging empathy and emotions. Oddly though, the one aspect that caught me was the fact that, in his notes, Joe Grim weighed 12st 6lbs, the same weight as myself (I’m taller than him so he probably wasn’t in great shape). I’ve never felt connected to anyone because of weight before, but I think it probably shows how deeply boxing has gotten into my head, that I now feel an affinity with anyone tipping the scales within a few pounds of myself.

It is perhaps unsurprising that during his psychiatric assessment, Grim was simply deemed to be of low cognitive and emotional intelligence, due to the professionals of the time simply not being able to imagine how he could possibly earn a living in the fashion he did. Again, we’re brought back to the questions: How do we interpret Joe Grim? How do we understand his motivations? How do we judge a society that allows him to be so publicly beaten for the entertainment of others? Why was his committal the point at which promoters finally felt as though they could/should no longer offer him matches? How do we deal with our own pain? How do we avoid passing our pain on to others?

How do we finish a book about a legend?

Stories don’t end. You know that. They don’t arc. They don’t do anything, except meander and continue and spin and wait to be rediscovered.

Joe Grim returned to the U.S. and boxed 20 more times up until 1913, but these are only statistics which tell us nothing of Grim as a man. That man doesn’t exist any longer; all we have are questionable reports and handed-down and half-remembered stories, whispers of whispers. Perhaps the most important aspect of what or who we believe Grim was, is what that idea causes us to think about ourselves.

Leave a reply to #107: ‘Pugilistic Queer Performance: Working Through and Working Out’ by Fintan Walsh – Writers on Boxing Cancel reply