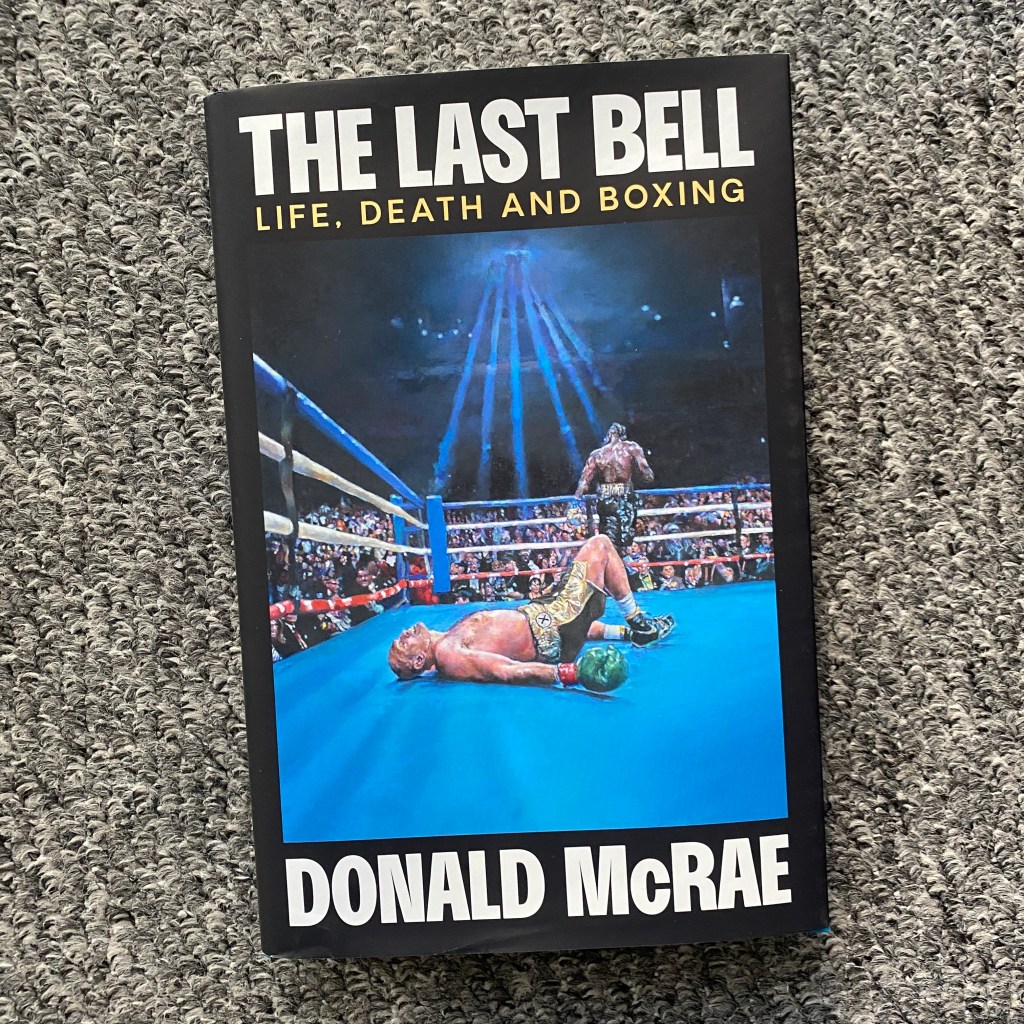

The Last Bell: Life, Death and Boxing, published by Simon and Schuster, is Donald McRae’s exploration of grief, sporting and political corruption, and is most likely his final book on the subject of boxing. The book cover features a painting by the wonderfully talented Amanda Kelley.

This book is a follow-up of sorts to McRae’s book Dark Trade, which has had a huge impact in and around the sport, and which allowed him to become a full-time writer:

I owe that gift to boxing. But our relationship is not easy. Boxing often disappoints and upsets me. It is as crooked and destructive as it is magnificent and transformative. All these years later, I am still trying to reconcile boxing’s paradoxes of hope and despair, salvation and ruin.

At its finest, boxing transcends sport to become epic and electrifying before reminding us that, above all else, the humanity of fighters resonates most.

This quote from the beginning of The Last Bell sums up very well his relationship to a sport which has not only brought him a very successful career, but a wealth of unreal experiences and rewarding and meaningful friendships. What it also does is put McRae into a tradition of boxing writing which I associate most with Hugh McIlvanney, who publicly embraced his misgivings with the sport and the business which surrounded it.

I sometimes catch myself arrogantly telling people that I have far less interest in the professional game than the amateurs. As though this is somehow nobler because it doesn’t involve the big name promoters and TV deals. Of course, huge parts of amateur boxing are geared toward producing professional fighters, and a number of amateur boxers have recently signed, or will soon sign, professional contracts. This point is on my mind a lot, because it’s bad enough getting to know boxers putting themselves at risk through three three-minute rounds, and the associated worry for their safety. I can’t imagine what it must be like to spend decades getting to know, intimately, a great number of boxers constantly putting themselves at risk in a business known for not always putting their welfare before cash returns.

The Last Bell charts McRae’s friendships with British cruiserweight Isaac Chamberlain and American super-lightweight Regis Prograis. Both of these boxers seem like thoughtful and remarkable characters outside of the ring, both well-read about their sport and keen to put their feelings and experiences into words (perhaps one day we’ll be lucky enough to feature their words in The Spit Bucket). There’s a temptation here to fall toward stereotypes of fighters and think of their personal insight as out of place, but I’ve only met a few boxers who aren’t aware of their self-perception and motivations. It seems pretty natural that a sport in which your opponent is constantly trying to hurt you will cause you to become contemplative. As with all aspects of life it’s often fame and fortune which turns people’s heads. Perhaps it’s this which makes Prograis, in particular, different.

One of McRae’s greatest skills as a writer is to tell peoples’ stories. This skill is what makes him one of my favourite writers, and A Man’s World and In Sunshine or in Shadow two of my favourite books in any genre. What links The Last Bell and Dark Trade are his descriptions of his personal life and the exploration of the effect that boxing has had on him as a writer and a husband, father, child and sibling. There are several references to his age in this book – McRae is the same age as my dad (and my close boxing and writing pal Chip), so I’m very familiar with conversations about dodgy knees and struggles with maintaining slim waistlines. It’s no wonder that thoughts of mortality and reflection follow these more physical issues.

Throughout stories of boxers being seriously injured or killed in the ring, McRae lays out the losses he and his family suffered in the past eight years – his sister, both his parents and his mother-in-law. His story of not being able to be present as his father passed, due to Covid restrictions, will resonate (unfortunately) with a huge number of people. It resonated with me as we lost my step-mum during the period that most restrictions were being lifted, though we weren’t able to visit her in hospital more than one person per day. A terrible toll on my dad and my sister, her daughter, in particular. I went through a period of writer’s block after, as we helped each other process what had happened – it’s no surprise that when I did finally get something on paper it was about grief.

Boxing can often feel like it represents the profound elements of life, but when people are dying around you it is clear that it is only a sport, and the fact that it is an entertainment industry is bound to become hugely frustrating. It might feel a small and unnecessary distinction but I think it’s important to always remember that it’s the fighters who represent and embody the profound. It’s through their actions that we see the strength of human spirit and endurance. Like Isaac Chamberlain refusing to give up on his dream in the face of the shambolic nature of small-hall promotion, or Oleksandr Usyk standing proudly in front of a ridiculously rude Tyson Fury as his country was being torn apart by war and his friends and family were dying.

A shadow in the shape of Saudi Arabia hangs over The Last Bell. McRae has been steadfast publicly about his own anger at so many boxing promoters and broadcasters jumping into bed with the General Entertainment Authority. He’s one of the few journalists who have maintained any form of integrity by standing firm on his beliefs that the nation’s human rights record cannot be ignored. Again, there are echoes of McIvanney’s voice in McRae’s writing as he attempts to interrogate his own motivations for loving a sport with so many dubious facets. A willingness to explore his own hypocrises. Boxing has a ridiculously fragile collective ego – it often reminds me of political or religious discourse in which any mention of anything negative casts you as the enemy of the collective. The sport would be much healthier with more room to discuss the impact of blindly taking money from the highest bidder. A lesson you might have thought it would have already learned throughout the twentieth century.

Such hypocrisy was embedded in my boxing writing. I lamented the damage and death that boxing caused. I complained about doping and gangsterism in boxing, I railed against the corruption and chaos of boxing. Yet I still came back for more again and again.

The great boxing writer Hugh McIlvanney had advised me thirty years before that hypocrisy and ambivalence would be my constant companions. He warned that boxing would also lead me to various hellholes, whether it was Las Vegas or a country led by a dictator or a fascist regime.

I often wonder if I do actually like boxing or whether it just feeds in me a need to be obsessed about something? The overlapping of boxers’ narratives allows me to travel decades and centuries into the past while looking at so many aspects of human behaviour. I suppose it’s important to remember to examine my own. Why I support a sport which encourages (or exacerbates) a feeling in its participants that they are willing to be hurt. Rewards this kind of blind (often uninformed) courage. Ignores the links to emotional pain and a desire to self-harm in exchange for a boosting of their self-esteem. A ‘well done’.

As with all of McRae’s books there’s far too much to cover in a blog post – plus, you should be buying the book and reading for yourself. I haven’t even mentioned the tragedy of Patrick Day, the insidious involvement of Daniel Kinahan, the broader arching brilliance of Oleksandr Usyk, and the takeover of Madison Square Garden by Amanda Serrano and Katie Taylor:

After a beautiful night, I asked myself a simple question: ‘Why couldn’t boxing always be this way?’

* While you’re here please consider checking out our boxing fanzine The Spit Bucket which contains some truly fantastic work from a collective of artists from around the globe. We’re currently looking for poetry, prose and visual art for issue six of the zine, which will be out in time to celebrate the project’s first birthday. Full submission guidelines (please read!) are available here on the website, and all previous issues are free to download, though please consider donating to The Ringside Charitable Trust as they aim to open the UK’s first residential care home for ex-boxers. Thanks.

Leave a comment