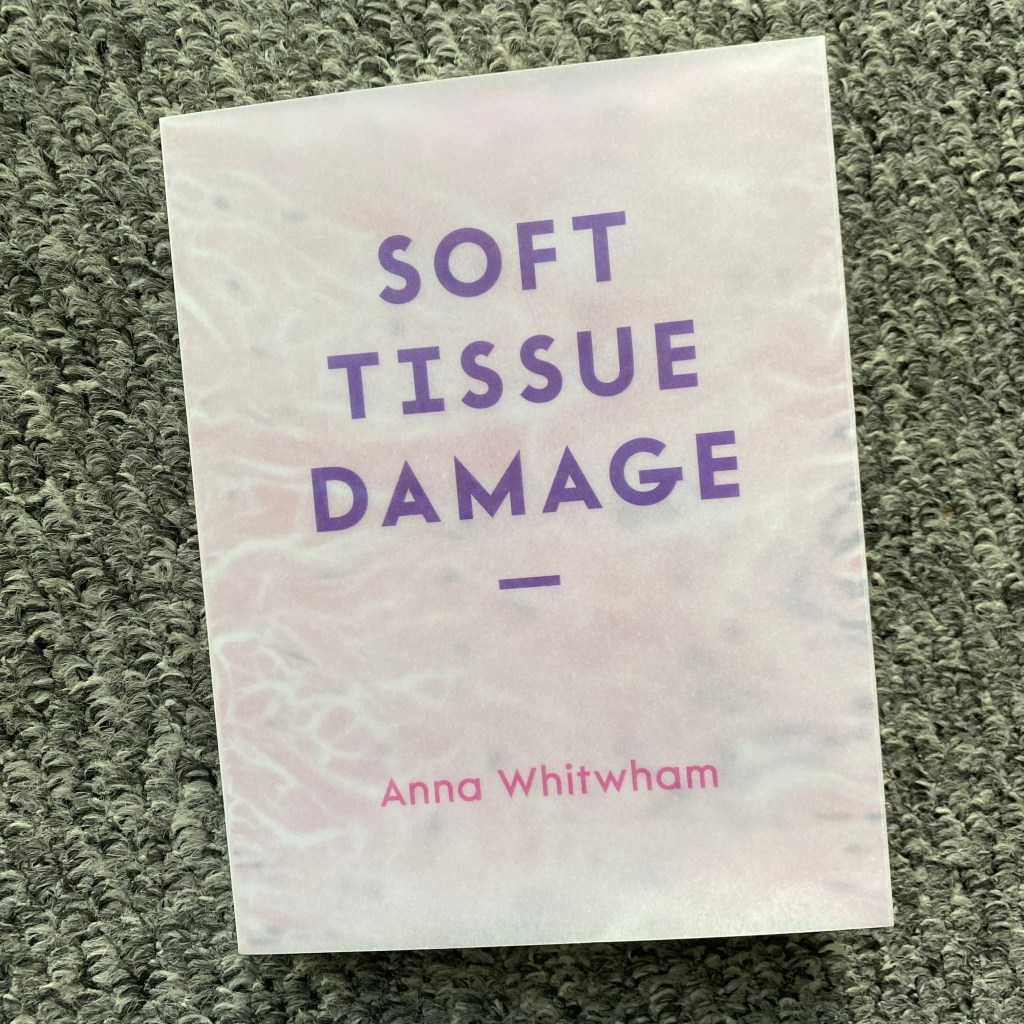

Soft Tissue Damage by Anna Whitwham (Rough Trade Books) is that rare but wonderful thing: a new boxing book to preorder, forget about, and then be surprised by as it falls through the letterbox.

This book falls into the category of boxing book which isn’t really ‘about’ boxing, or boxers, promoters, venues, or famous bouts. Instead it uses boxing as a way of framing / contextualising a powerful life experience – in this case, Whitwham grieving for her deceased mother. Of course, boxing as an act is ripe for this type of introspection – even recreational boxers are encouraged (forced?) to question their ability to push through pain barriers. To continue when that option seems insurmountable.

What Soft Tissue Damage does well is to highlight the links and similarities between training in a boxing gym and intimate care for ill or less-abled individuals. Anyone looking to train at any level beyond keep-fit classes will have to quickly resign themselves to being touched, often in places they may not have considered. Hands will need to be held out to be wrapped, sweaty faces and bloodied, snotty noses presented to be wiped, tender ribs to be felt, mouths opened for the fingers of others to enter and retrieve mouth guards. The acts of care from trainer to boxer are still written about relatively seldom, and these forms of intimacy perhaps still feel too precious / embarrassing to talk about for many. Shared experiences too raw for public consumption – more raw than black eyes, broken noses, and urinating blood.

As an extension of these acts of care Whitwham’s writing is at its strongest and most revealing when she examines the intergenerational relationships between the women and girls in her family. Switching and flipping roles between mother, daughter, sibling, carer. This examination, of course, carries over to how she found and carved her own space, as a woman, in a boxing gym, but these aspects are not reliant on one another.

Boxing training encourages in all of us an embracing of rituals and routine, which for many can also provide a space to deal with grief. Perhaps what we need most when processing grief is a method for working through these immense emotions incrementally: in months, weeks, days, hours, three-minute rounds. There are few worse feelings (in a gym) than knowing your fitness / technical prowess has slipped when failing to perform as you might wish. But if you can be pragmatic, and kind to yourself, it becomes impossible to lie to yourself that you have not moved forward in some manner. It should be possible to find some comfort in this.

(I’ve only recently started reading up on Henri Bergson’s theories so I won’t claim to have any full understanding here, but his ideas around embracing process to gain a more fulfilling understanding of time seem very relevant here.)

Something I’ve been considering in my own writing about boxing (and more widely) is whether (as someone who has never boxed as a carded amateur or professional) it is possible to add insight in the eyes of those who have. And whether it’s possible to do so without falling back to cliches. What is boxing anyway if not an assemblage of cliches? Tens of thousands of jabs thrown (in exactly the same manner) at a heavy bag feels like at attempt at becoming a punching automaton. How is it possible to respond originally to a pastime in which a collective mindset and physical actions are part of the attraction?

Similarly, if we, as writers, are being read by those with only a passing interest how do we avoid falling for the trappings of easily achievable shock factors? A lot of my writing has previously openly tackled the violence I’ve witnessed in my life and it often feels incredibly easy to bloody-up the content for readers who are intrigued by that sort of thing as a result of being lucky enough not to have witnessed it. I’ve never spoken with Whitwham before but I’m sure the temptation to shock (the all too easily shockable) literary audiences must have hung over the writing of this book. Particularly as a woman writing about her own urges toward violent behaviour.

What shines through this book is a sentiment which I know most recreational boxers share (particularly women), which is finding a sense of community in a gym. Whitwham’s own journey has clearly allowed her to find her ‘tribe’, and to reconcile her relationship to a certain type of man:

“Men are still new to me. But boxing has become a way of assembling the kind I want in my life. I am putting a world back together, reshaping the scaffolds of a life that lost its centre. I feel nurtured. I don’t find their machismo brittle or threatening. They welcome my body, my ideas. They celebrate me, and the other women here. They get me to play to my strengths – my grace, lightness – to dance in the ring, to tell stories.”

While you’re here please consider checking out our boxing fanzine The Spit Bucket which contains some truly fantastic work from a collective of artists from around the globe. We’re currently looking for poetry, prose and visual art for issue six of the zine, which will be out in time to celebrate the project’s first birthday. Full submission guidelines (please read!) are available here on the website, and all previous issues are free to download, though please consider donating to The Ringside Charitable Trust as they aim to open the UK’s first residential care home for ex-boxers. Thanks.

Leave a comment