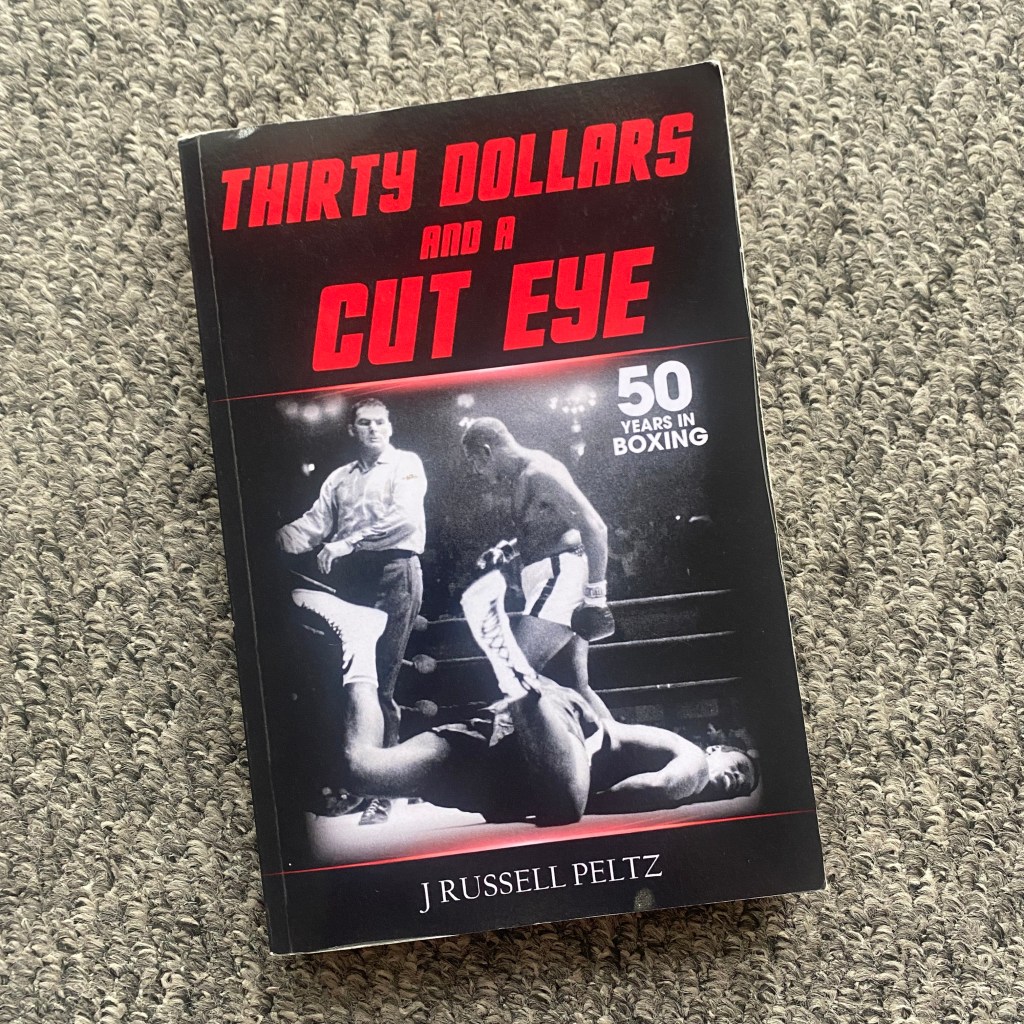

Thirty Dollars and a Cut Eye is J. Russell Peltz’s look back at his 50-year career as a boxing promoter and matchmaker.

Peltz took his first steps as a promoter in 1969, at the now legendary Blue Horizon in north Philadelphia. At the age of 22 this was, and still would be, a very bold move, but Peltz is one of those irregular characters who have a firm idea of their dream vocation from a young age; he fell in love with the sport as a teenager watching bouts with his father, both live and on TV.

The insights into what the Blue Horizon was like as a venue during the 1970s and 80s were definitely a highlight of this book for me as I’ve read a lot about it in other boxing books. It has almost mythical status now (no doubt viewed, slightly, through rose-tinted glasses) and seems to embody a time for boxing that we can’t return to. No doubt though, the patrons of the 1970-era Horizon were regularly told, by the older heads in the crowd, that the skills on display were nothing compared to those of the 50s/40s/30s…

I always enjoy reading about these sorts of venues as they play such an important part in the lives and identities of the local communities. The Horizon, incidentally, seems almost identical to London’s York Hall, with its three-sided balcony looming over the ring, and a similar capacity of around 1500. York Hall’s reputation seems to have been bolstered in the past few years simply because there aren’t any ‘small halls’ left with the same sort of history. I’ve heard similar stories of amazing nights at York Hall; of boxers laying everything on the line for area titles. Though, all too often, the venue and its reputation are let down by conservative matchmaking and the plethora of ‘contender v journeyman’ bouts (and their predictable outcomes).

(Argentina’s mythical Luna Park also features in this book, which is a joy.)

It seems as though Peltz was responsible for the resurgence of the Horizon and the avoidance of the venue permanently ‘going dark’ during the 1960s. Throughout the book he reiterates his motivations to make the best, and most entertaining, fights for the spectators; not for the boxers and their management teams. Early on he did this by matching fighters from different parts of Philadelphia, convinced that local rivalries would boost tickets sales, while at the same time reestablish pride in a flagging local boxing scene which had seen promoters and managers keeping local fighters from meeting.

The book goes on to chart the highs and lows of living and breathing professional boxing, perhaps at times in a little too much detail: there are a lot of facts and figures in this book, even for one about ‘the sweet science’. As Peltz acknowledges at the end of the book, he wrote the manuscript he wanted without trying to please, so fair play to him for sticking to a singular vision and for being so (seemingly) honest about how much he made and lost on so many of his promotions through the decades. I, however, was a little overwhelmed by the dollar signs and win/loss records of the local boxers.

(Similarly, I find it hard to mention any of the boxers he’s worked with as there are simply too many to narrow it down.)

Peltz saw the rise and fall of many TV networks and venues as boxing wandered across the US in search of the biggest purses. This aspect of the book in particular highlights how fragile the business is as it wholeheartedly throws itself into broadcast deals, with very few back-up plans when the deals eventually evaporate. To paraphrase UFC‘s CEO, Dana White: ‘boxing’ approaches every promotion as though it is its last. This sentiment highlights how the general practices of the business are usually so at odds with individuals like Peltz, whose model involves maintaining ‘small hall’ venues (often at a loss) as a space to nurture young talent.

Of course, there are many tales of dodgy dealings and underhanded tactics from promoters, managers and boxers alike and no one comes out of these smelling very sweet. Again, there’s a good level of honesty from Peltz as he admits to many mistakes, either passing up opportunities with future world champions, or not doing the right thing, financially, by a boxer. I think he also avoids the enormous temptation to do too much score-settling and treats most in the book fairly.

As Peltz sees it, the biggest problem facing professional boxing is the confusion over the sheer number of sanctioning body titles that are now available, and TV’s obsession with having even the most minor of baubles attached to a broadcast. Not only does this distract boxers from fighting locally for more historied titles, but it creates a confusion in the heads of the fans and a watering down of the importance of any title.

Along with this he points to the breakdown of traditional media as a big issue for the promotion of all but the biggest boxing cards: now, instead of readers of newspapers happening across fight reports in amongst coverage of other sports, coverage is splintered across sport-specific websites. Typically, fans will now only visit sites which focus on their favourite sports, with little or no opportunity for crossover coverage. It’s no wonder that professional boxers are increasingly feeling pressured to shout ever louder on social media, to drum up interest in fights, even if that means doing and saying stuff that is ultimately regrettable.

Leave a comment