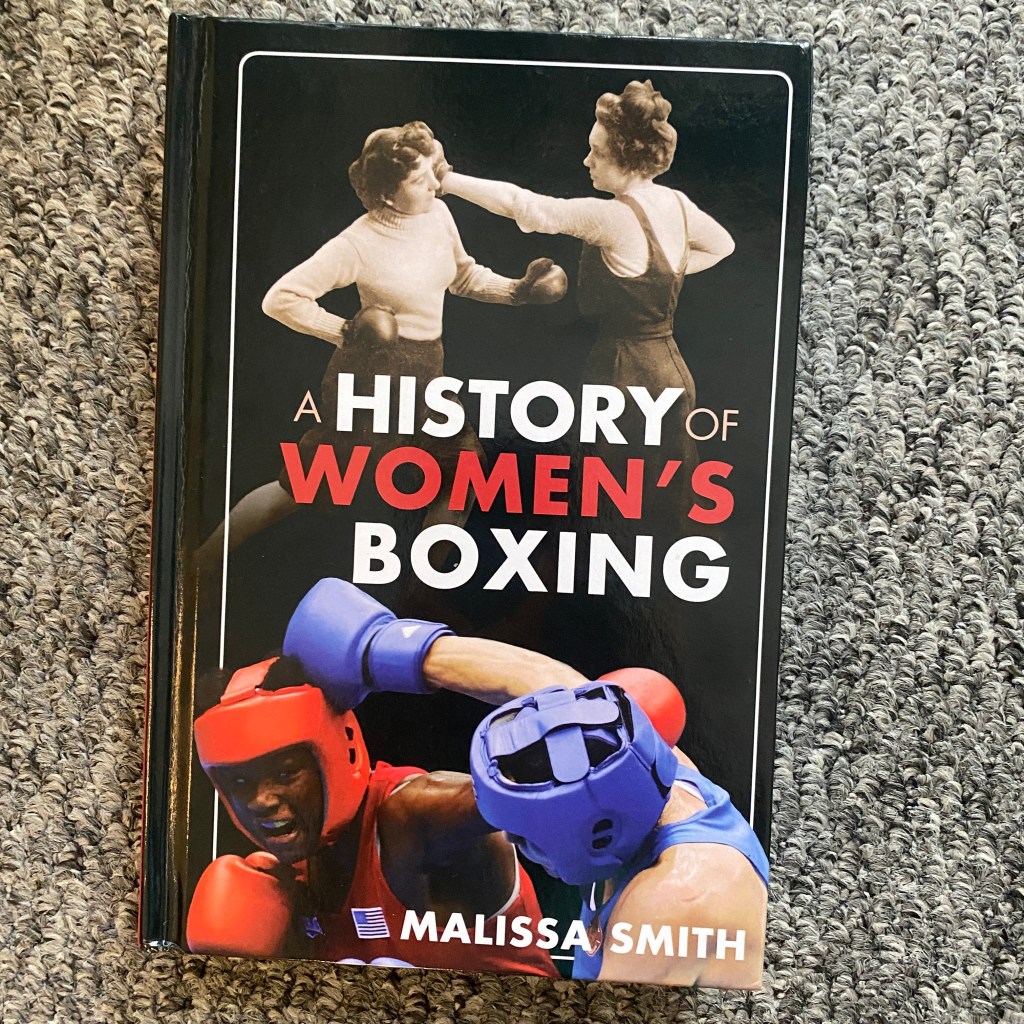

‘A History of Women’s Boxing’ by Malissa Smith is the defining publication of women’s participation in boxing, published by Rowman and Littlefield in 2014.

Extraordinarily well researched, this book brings the reader details and stories of women prizefighters from as early as 1722, when Hannah Hyfield challenged Elizabeth Wilkinson Stokes to meet her at the Bear Garden in London, right through to the IOC finally allowing women to compete at the 2012 Olympic Games.

In between these two points in time exists such a vast number of women who have all tried and failed to be recognised on an equal footing to their male counterparts that there seems no argument that there was a consistent and prejudiced social attempt to bury and deny their stories. If there hadn’t been such a concerted effort at denial then the women in this book would be much better known, credited and respected.

This blog doesn’t really allow a sufficient space to properly cover academic-style texts so I’m only ever going to be able to hint at what awaits the reader; I will say though, that anyone with an interest in the history of the sport should read this book. Regardless of the overarching gendered theme, the book highlights just how corrupt and bent the business of boxing can be in treating its participants and fans, and also how ridiculously slow it can be to embrace change and new audiences.

One of the points made by Smith in the book is that perhaps the closest the women boxers of the 1970s and 80s ever came to being treated equally was when they began to be overmatched, underpaid and generally disrespected by promoters of all positions of power. Of course this didn’t reflect the treatment of the stars of the male code at the time, but it did often put them on a par with the men at the bottom of boxing’s greased ladders.

From Hyfield and Wilkinson Stokes of the 1720s; to Hattie Stewart of the 1880s; Barbara Buttrick and Jo Ann Hagen of the 1940s and 50s; Jackie Tonawanda and Marian ‘Lady Tyger’ Trimiar of the 1970s and 80s; Christy Martin, Lucia Rijker and Jane Couch of the 1990s; it is irrefutable that any lack of participation of women in serious boxing bouts, amateur or professional, was never down to a lack of willing boxers and athletes. It is clear from the evidence collected in this book that the barriers to competing were first in put in place by puritanical (British Georgian and Victorian) social beliefs, and later by the established governing bodies controlling access to amateur contests and professional prize rings.

I’ve been meaning to read this book for a while, and was prompted to do so now as Smith has just had a follow-up book published, called ‘The Promise of Women’s Boxing’, reflecting on the ten years since the publication of this book. It was very interesting reading under a contemporary context in which women’s boxing is enjoying huge success and popularity.

As I finished the book today I saw a brief promo for young British bantamweight Fran Hennessy who as a three bout novice is enjoying the same publicity and build-up to her career as any young male fighter might dream of. Hennessy is of course the daughter of established British promoter Mick Hennessy, but even so, I think this sort of start to a professional career, including televised bouts, for a boxer without a medal-laden amateur career, would surely have been unimaginable back in the early 2010s when Smith started writing this book.

We’ve all come a long way:

Boxing has persevered as a sport since the 1720s, with women among the first to embrace the wonders of the prize ring. That spirit of adventure continues to this day – and while the sport will inevitably twist and turn, the women of the squared circle will be there every step of the way.

Leave a comment