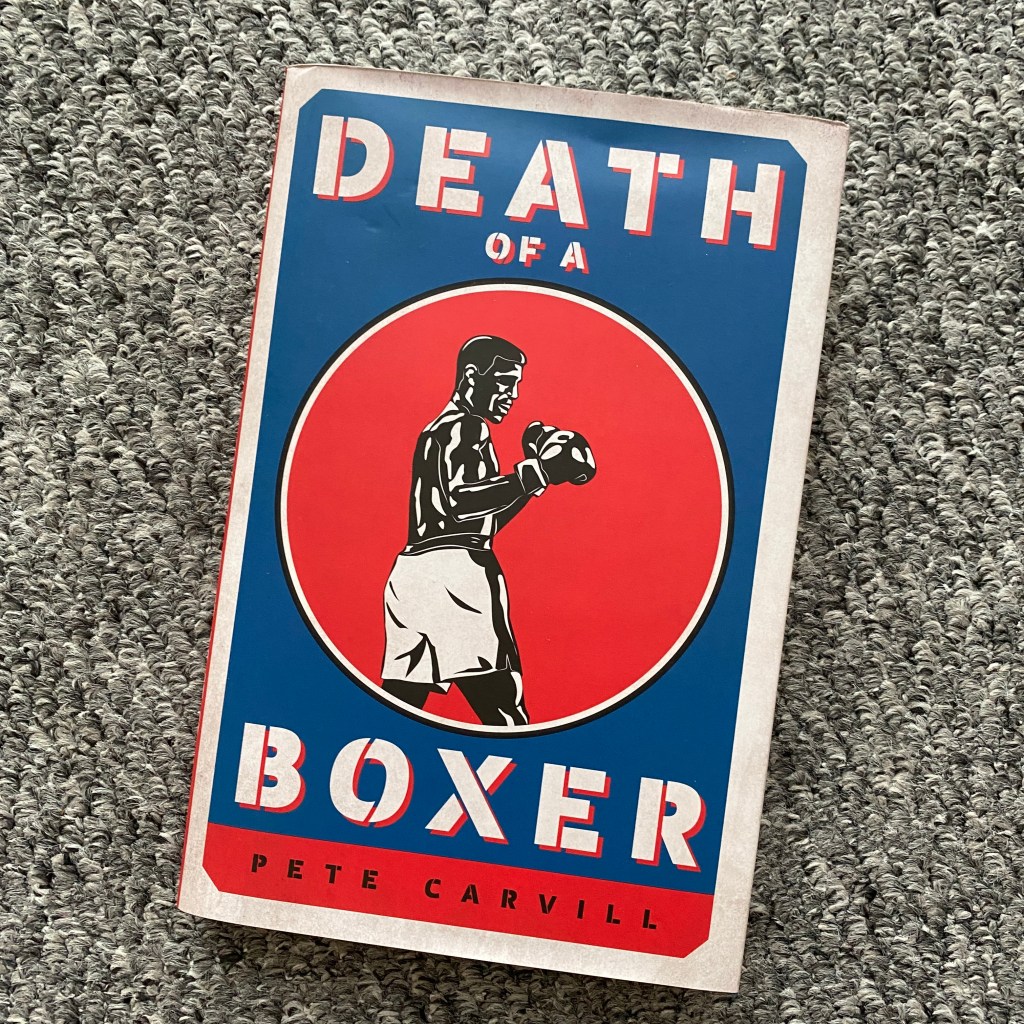

‘Death of a Boxer’ is Pete Carvill’s ode (or rather series of odes) to boxing, a collection of essays outlining his relationship with the sport. The book was published by Biteback Publishing, February 2024.

Carvill walks us through what is now a strained association with the noble art, exploring themes of masculinity; the importance of the people holding the sport together at its grass roots; the murkier sides of the business and its finances; research into CTE and brain trauma from being punched repeatedly; what boxers do when they approach the end of their careers; and what we do as fans when we can’t escape the realities of watching athletes damage their health for our entertainment.

Carvill’s book is archetypal in that it tackles the same overarching themes as a great many of the books covered on this blog (and, no doubt, in the many I am yet to read). That’s not to say that the book is a cliché, rather that it highlights how simple boxing is as a concept, while eliciting very strong emotions and hiding an unnecessarily complex business structure that is still baffling to many who are familiar with it.

One interesting angle that this book takes is that Carvill has lived in Berlin, Germany for many years, so his perspective as a fan and writer not based in Britain or America adds a unique (at least on this blog) viewpoint of the professional sport. It’s easy to forget sometimes that professional boxing happens outside of these two countries (at least until Saudi Arabia takes over completely), and the role that Germany played in the sport in the not-too-distant past.

Whilst this book is aimed at those deeply entrenched in the sport already, Carvill regularly goes to lengths to explain and break down this confusing business to newbies. This also marks the book out from most publications. I found this aspect intriguing as it reflects, a lot, mine and my wife’s feelings toward the sport (and indeed those of many others I know), highlighting as it does the conflict between being very uneasy with the dangers faced by its participants and the desire to ‘convert’ everyone around us into at least giving boxing a chance. We’re almost evangelical about seeing the beauty behind the facade of brutality, knowing full well that behind that beauty is often actual internal brutality.

The ‘death’ in the title refers to two boxers it seems, the first being the tragic and wholly preventable passing in 2016 of Scottish welterweight ‘Iron’ Mike Towell. Towell died from injuries sustained while fighting Dale Evans in Glasgow, and as Carvill highlights through his research, this sad event could have been avoided with stricter regulation and better communication between health services and governing bodies.

Now, this is not a criticism of this book, but rather an accumulation of feeling from reading so much material in a relatively short space of time – but do we get to pay our penance simply by repeating the names of the fallen? As important as this process is in not forgetting those who paid the ultimate price, it sometimes feels as though, as fans, we’re taking the easy way out by paying tribute to the dead while just continuing to watch the sport.

I think that perhaps the root of this sentiment is Hugh McIlvanney’s beautiful tribute to Welsh bantamweight Johnny Owen, in which he so perfectly confronts the contradictions of loving a sport that can so easily claim the lives of its protagonists. These questions are prominent in my mind as I consider whether I want to dedicate time to writing about boxing.

The second ‘death’ is that of Carvill’s own self-identity as a boxer. The book opens with a passage in which the author has to accept that he is simply too old and slow to avoid punches, and to make the sensible decision to hang up his sparring gloves. It’s funny how books will slap you in the face as they reflect exactly what’s going on in your mind, in the form of anxiety and paranoia. For context, I am not and have never been a boxer, but I have always been very athletic and the irony haunts me every time I’m in the gym that, at 43, my reflexes are slowing and my legs are just getting heavier.

I’m still in very good shape for my age, it’s just that my age is too old for boxing against younger opponents. As Carvill says in this book, 32 is old for a boxer, and I’m a decade beyond that. Though, this is what I love about my local amateur gym and boxing in general, that there’s still a space for this ever-aging and -slowing version of myself. I just wish I could show the 25-year-olds in the gym how fast I was at their age… but I suppose it’s best to process that thought and realise the futility of it. I’ll just try and grow old gracefully and be glad of a space to go and hit a bag with a decreasing tattoo.

Leave a comment