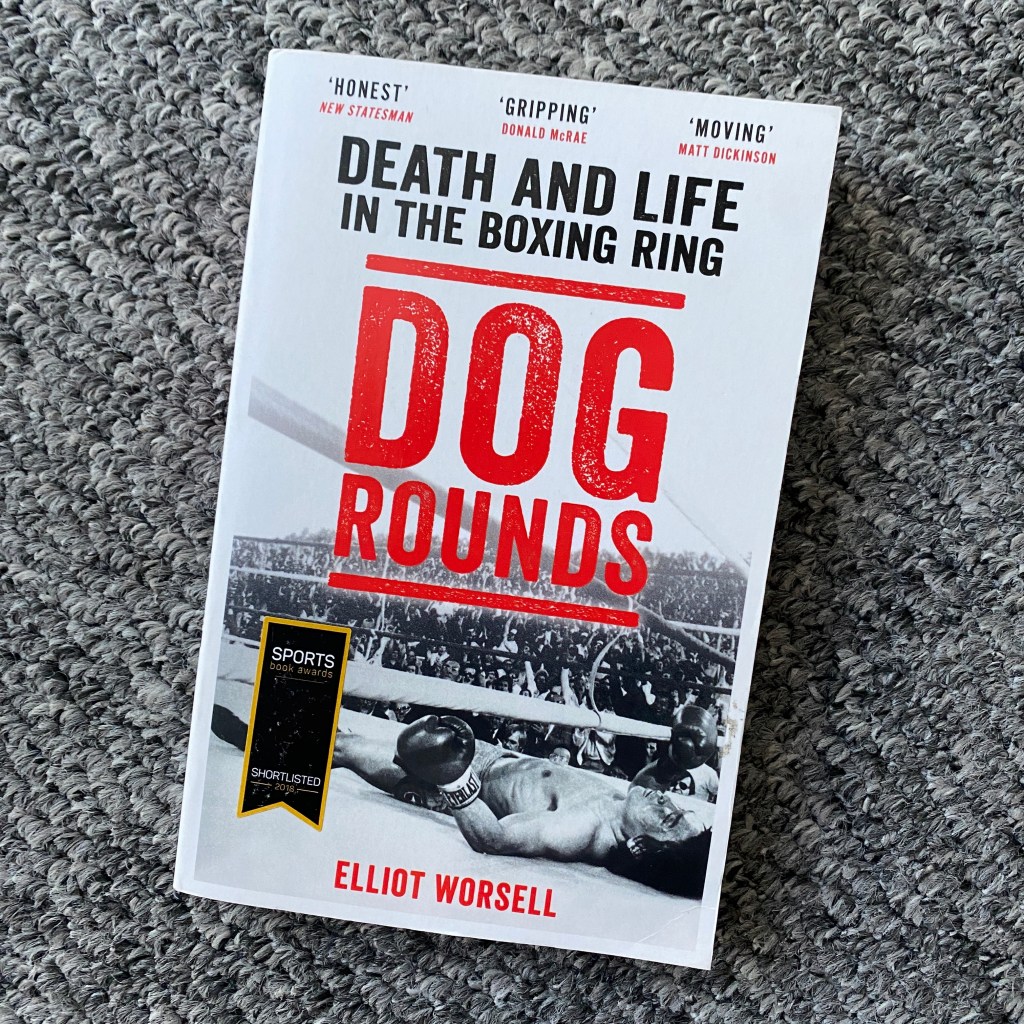

‘Dog Rounds – Death and Life in the Boxing Ring’ is Elliot Worsell’s commendable, yet perhaps uncomfortable, exploration of the darkest side of the sport of boxing: when tragedy strikes and a boxer is profoundly injured or killed.

The book is framed by the ill-fated bout between Chris Eubank Jr and Nick Blackwell, March 2016, after which Blackwell fell into a coma, fortunately regaining consciousness, though never fully recovering from his injuries. Under the shadow of this fight (and that of Eubank Snr’s fateful clash with Michael Watson), Worsell, through interviews with the boxers involved, explores the consequences and legacies of bouts in which boxers have been killed.

[A quick note: On this blog, I usually try to give a brief overview of books, especially listing the boxers mentioned so that readers can follow up my posts if the books feature fighters they have a particular interest in. I have tried, numerous times, to list the boxers covered in this book, but each time the lists have seemed crass and/or unsympathetic toward the boxers who have been killed or suffered life changing injuries, and those living within the guilt of having a hand in those injuries. I’ve abandoned this approach.]

Alongside a genuine attempt to reveal the human aspect of these sporting tragedies exists Worsell’s personal exploration of his own place in Blackwell’s fate. Leading up to the fight Worsell was acting as press agent for various promotions and, as does everyone else in that position, he knew that any stoking of rivalries and feuding between fighters would lead directly to an increase in ticket sales.

Worsell returns throughout to questioning his motivations and desire to be involved with such a murky business, before delving deeper into this particular subject at the end of the book, to reveal that this book was already in progress when Blackwell, by this point a friend, almost lost his life and forced his and Eubank Jnr’s story into such a prominent and unenvied position.

It’s always refreshing when those close to boxing decide that their career ambitions should take second place to an obligation to speak out and try to make a positive difference to a sport (or business) that often seems intent on destroying itself. Though it is equally disheartening when you, inevitably, reach the point at which those people express a resignation that their pleas will probably just be ignored by those whose only aspiration is to make a financial profit, or gain public notoriety.

Since becoming more involved with amateur boxing, as a spectator, and recently qualifying as a judge, I’ve been asking myself similar questions about my own role within boxing. It’s not always easy to reconcile that a huge amount of my spare time is engaged with supporting an activity which can, in extreme cases, be very harmful to the health and wellbeing of the participants. Why do I spend so much time watching (often young) people punch each other in the head? Why do I voluntarily give my time to sit in as an official to ensure that amateur events can take place; events that so many would condemn as out of step with a ‘civilised’ society?

I don’t have coherent answers for these questions, except for pointing to all the wonderful people that I know within boxing, and the positive impact it seems to have on so many involved. There is, of course, a huge difference between amateur and professional boxing, but the two are intrinsically linked nowadays, with almost no pro boxers plying their trade without some sort of amateur career.

Returning to the subject of promoting fights. No book of this nature could be written without mention of Emile Griffith winning the world welterweight title fight from Benny ‘Kid’ Paret in 1962, after which Paret sadly died as a result of injuries sustained in the bout. As with most of the boxers featured in ‘Dog Rounds’, Griffith suffered hugely because of the guilt surrounding his role in Paret’s death, and the way the media latched on to referring to Griffith as a ‘killer’.

The media’s portrayal of Griffith was also influenced by the fact that, before the fight, Paret had used homophobic slurs toward him (Griffith was a bisexual man living in the USA, at a time when this was still illegal in most states), and the overriding narrative was that Griffith had sought to punish Paret, leading to excessive force in the fight.

Aspects of this unfortunate story were echoed in 2021 when one of this book’s main protagonists, Chris Eubank Jnr, met Liam Smith in a middleweight clash in Manchester. In the build-up to the fight Smith questioned Eubank Jnr’s sexuality, in a completely misguided attempt to unsettle his opponent. Aside from being simply abhorrent, in the idea that it is ok to insult someone by simply suggesting they aren’t heterosexual (Eubank Jnr would later show up at public events wearing rainbow colours in solidarity to those upset at these suggestions), it also highlighted that, in the UK at least, boxing is the only professional sport in which an athlete would feel buoyed enough to make such a public statement.

I don’t think it can be denied that this is because of boxing’s longstanding tradition of stoking any potential flame until there is an, often fabricated, inferno raging between opponents. It’s very refreshing to read the considered thoughts of someone that has played a part in fanning these flames to sell a fight, and who has come out reflecting so deeply on it.

It is probably obvious that this book is not going to be a ‘breezy’ read, and at times I found it hard to continue reading it. I can now name several current and recently retired pro boxers as, if not friends, then definitely more than acquaintances, and this has simply made it impossible to not imagine the impact that serious injuries would have on their friends, gym mates and family members. And from a selfish point of view on myself. (I recently went to see my pal Obi Egbunike fight Lee Cutler for the English super welterweight title, and as Cutler ripped away to Obi’s body in the middle rounds I’ve never wanted a fight to just stop more in my life.)

As hard as it is to read the book in parts, I can’t imagine how tough it was to research, to dedicate so much time to distressing stories in which lives end and livelihoods come to an end. Worsell touches on this in the book when he recognises that he could probably only have written it as a young person. I can completely understand this; as a 42 year-old, I just can’t imagine having any desire to go back and watch footage of bouts knowing that tragedy is going to occur. Sporting snuff films.

My relationship to boxing has changed a lot in recent years and it is almost certainly because of my age. I don’t think it’s a surprise that I got into the training side of it at an age when I was already to old to consider competing at any level. This has meant that sparring is almost never mentioned to me. I’m glad of this, as I just don’t want to be hitting anyone, or getting hit anymore. I’m also glad that I played contact sports when I was young, and experienced enough drama (violence) as a young man to have gotten it out of my system to the point that white collar boxing isn’t a temptation. That iteration of the sport seems ridiculously hazardous to me.

Finally, and just because it ties into my trip to Bournemouth to watch Obi box, is the mention of Mick Hennessy in the book. Hennessy was Nick Blackwell’s promoter at the time of his bout with Eubank Jnr, and he consequently spent a great deal of time at Blackwell’s bedside at St Mary’s hospital in London. Mick was accompanied (I don’t know how often) by his children Michael and Fran, both of whom have gone onto become professional boxers. Fran actually won her second professional bout on the same card as Obi.

This one small scene in the book where they are all around Blackwell’s bed encapsulates this dilemma perfectly. How can you live a life attached to such a brutal and unforgiving sport, be sitting at the bedside of a boxer who is in a coma due to injuries suffered during a fight, and not simply refuse to allow your children to ever enter a boxing gym again? I’m not writing this in judgement of Mick, but rather highlighting how monumental these questions often are. It’s perhaps this inherent drama surrounding the sport that offers an insight as to why it is so attractive as a spectacle?

If you’d like to know more about Elliot Worsell as a writer, then I can highly recommend listening to his appearance on Tris Dixon’s Boxing Life Podcast. Series 5, ep.21.

Leave a comment