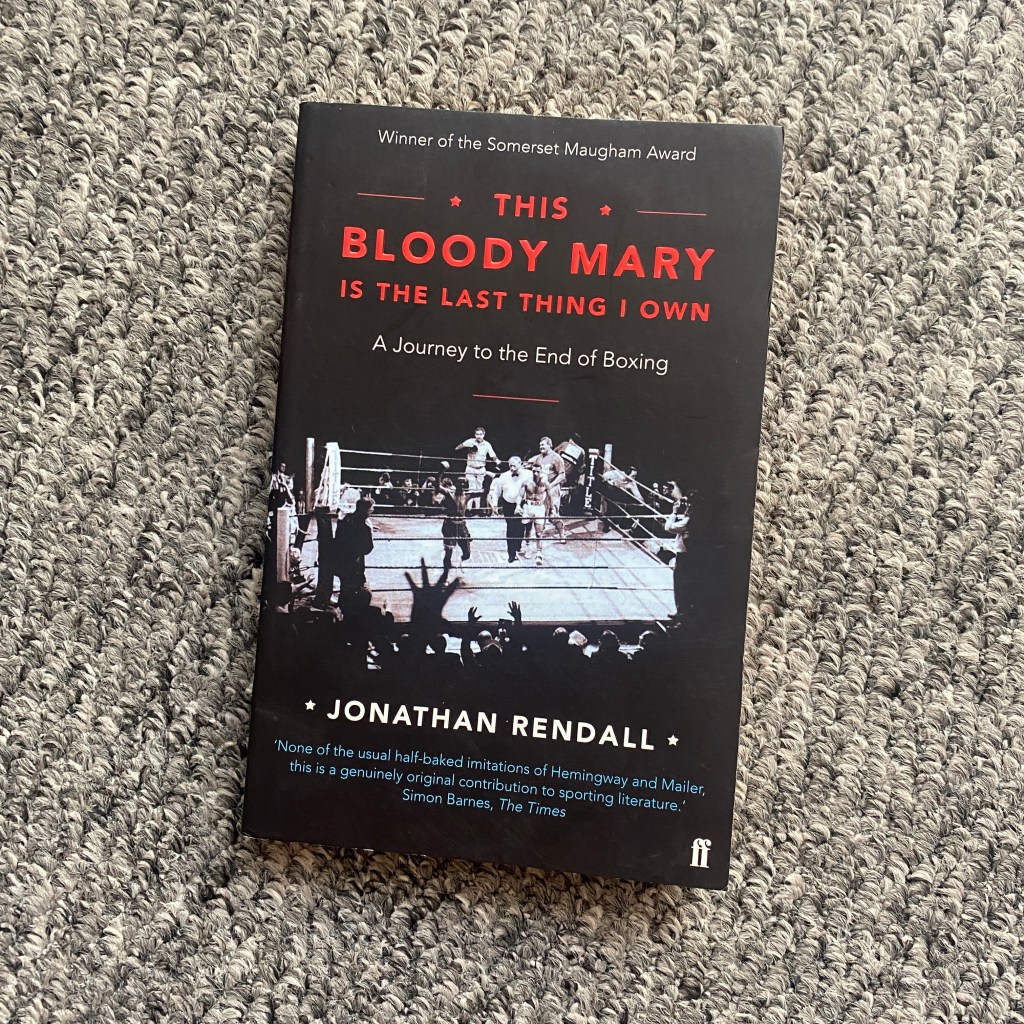

‘This Bloody Mary is the Last Thing I Own – A Journey to the End of Boxing’ is Jonathan Rendall’s retelling of his own, slightly odd, fortuitous and short-lived, ramble through boxing.

Books and stories like this are always going to appeal to me as I recognise myself in any author that has no ‘real’ place in boxing, either as a boxer, a trainer, a manager, or a promoter, but is nonetheless drawn in as a committed observer. In this vein there are similarities between this book and Ian Probert’s ‘Rope Burns’, in that Rendall, too, found himself in a relatively prominent position inside British Boxing, first as a boxing correspondent then as the manager of Colin ‘Sweet C’ McMillan, seemingly by accident. The honest and humble narrative tone that Rendall takes throughout this book makes his involvement in the sport in general, and as manager of an exciting British featherweight prospect, all the more ridiculous.

I think something that links all books on this blog which concentrate on the careers of fighters is just how much their career opportunities and trajectories apparently rely of complete luck; randomly meeting someone at a press conference, or a gym, or petrol station. Even after becoming so familiar with the lives and professions of so many boxers, I still can’t believe that so much of the sport is (or has been) conducted on such an ad hoc basis. In a business where so much is at risk physically, it is crazy that boxers have had to put their total faith in people with little or no experience.

As I mention, Rendall acknowledges his own shortcomings in terms of experience throughout, and it really should have been up to the BBBoC to look out for the boxers’ welfare and see that they put experienced operators in charge of their livelihoods and wellbeing. This book covers the same era in which Barry Hearn was taking his first steps into boxing promotion, which also highlights that often the only qualification needed to become integral to boxing is the right amount of cash or bravado. Hearn himself has since admitted publicly how naive he was going into the sport.

A highlight of this book is the way Rendall writes about and captures a variety of people who, in this circumstance, happen to be boxers. Luckily for us he was in the right place at the right time, to compile brief portraits of boxing legends Jack ‘Kid’ Berg and Kid Chocolate, both of whom died without full recognition of their achievements, and living lives far from what you might expect of greats of a sport awash with so much money (unless of course you’ve read a lot of boxing books and are aware of just how common it is). These small sketches are all the richer for attempting to capture a realistic view of their personalities, rather than skirting around the difficulties that this approach highlights.

For different reasons both boxers were unable to leave the past and fully process what the world had become around them. Perhaps though, for two men who were very well known and feted in an era when industry, innovation and fashion were progressing so rapidly, it was inevitable that even these two enormously energetic men were going to run out of momentum and be left behind by the society they felt would roll on, unchanged, indefinitely.

There is a small but welcome mention for Vernon ‘The Entertainer’ Vanriel, who Rendall mentions as a favourite boxer of his, and who is someone I would put into a similar category as Berg and Chocolate, not for what he achieved as a boxer, but for how drastically his life spiralled after he finished boxing, and for how shamefully he was dropped and forgotten.

Eventually Rendall became disillusioned enough with the sport that he decided to walk away before it consumed him. I think anyone who has been involved with any creative or entertainment industry will recognise the the curse of ‘networking’ in order to progress, and the toll that can have on a person, though boxing seems to be particularly bad for people stepping on each other’s necks, even without knowing they’re doing it. It would drain anyone to eventually realise that people are selling you a dream, not for your benefit, but so they can ride your coattails, either all the way to the summit or just far enough to jump clear of you when you falter, and move onto the next prospect.

(Imagine Super Mario jumping <LEFT and >RIGHT from cloud to cloud numerous times, only to progress a single platform ^UP, still nowhere near rescuing The Princess.)

I really enjoyed Rendall’s writing here and it’s been a while since I’ve read a sports book where so much thought has been put into the structure of the writing. In part one of the book the prose mirrors the author’s lack of knowledge and experience, and anxiety about ‘being found out’. In part two, the style becomes much more confident, as he finds his way in the sport and gets to grips (mostly) with guiding Colin McMillan’s career. Part three is built upon a much more rapid style of writing, at times overwhelmed and confused, as the business of boxing becomes too much to live with and a paranoia begins to seep in.

As a boxing book this one stands out for not having a tragic ending. Tellingly, maybe, it’s because Rendall gets out before any real damage is done. A valuable lesson, perhaps.

Leave a comment