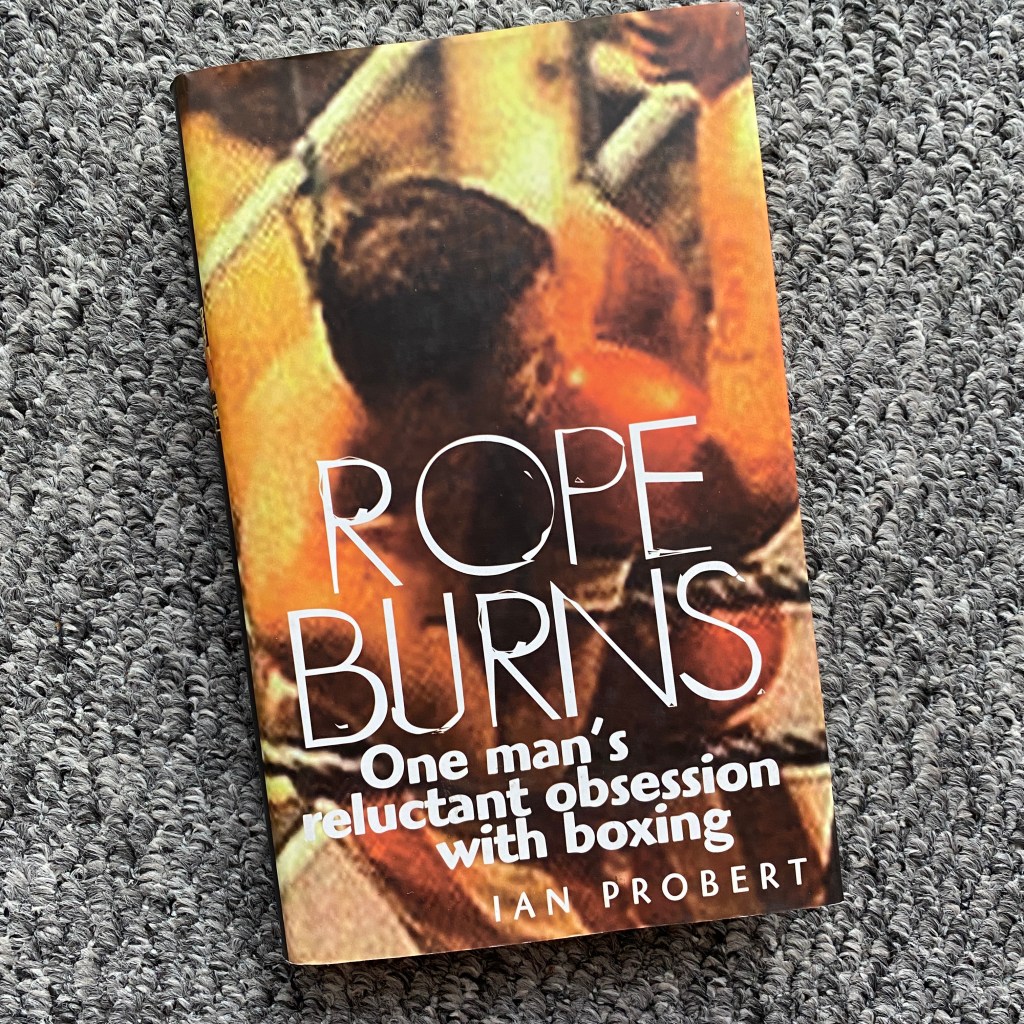

‘Rope Burns’ is Ian Probert’s story of a life stalked, shadowed and punctuated by professional boxing.

Probert describes himself as a reluctant boxing fan and this book is an attempt to avoid writing about boxing; so much so that if it weren’t for the ‘Rules of Boxing’ which end each chapter, you might wonder during the first half of the book when or if the author will ever get around to writing about the sport.

I don’t know if there is any direct intention on the author’s part to describe a universal or common boxing fan experience, or whether it is just a coincidence, but I think the majority of even the most committed boxing fans would recognise their own relationship to the sport in this book. I feel there’s a general misconception that all keen boxing fans are obsessives when it comes to fight dates, venues and promoters; the reality is that, for most of us, boxing explodes into our lives in bursts, on the shoulders of individual boxers, or the sudden emergence of a pool of talent in a particular weight division.

For a lot of us it is necessary to get a few years or decades older before we can dedicate the large number of weekends necessary to follow boxing’s ever-growing number of governing bodies and championship titles. Those who follow boxing faithfully from a young age are of a special breed, one that I’ve never been a part of. I was too busy trying to avoid my life through socialising until my late thirties, to pay attention to any boxing other than the biggest bouts of the early-2000s. This has resulted in large gaps in my knowledge of the sport.

By his own admittance, if Ian Probert hadn’t ‘accidentally’ become a boxing correspondent for the Sunday Sport, then he too would have likely only sporadically come into contact with boxing throughout his life. As someone who in recent years has come into contact with more boxers than I’d ever have expected, I can understand how quickly and easily the author became engulfed in the world of boxing; almost without exception, every boxer, trainer and manager I’ve met has been hugely welcoming and generous with their time.

Almost the entire first half of the book is dedicated to the intermittent but intense joy of randomly discovering that an acquaintance or friend is a fellow boxing fan, so it’s no surprise that Probert later found the chance to work in an industry parallel to the sport so intoxicating. It’s also no surprise that this intoxication eventually became untenable when combined with the journalistic (bullshit-pedalling) methods employed by the Sunday Sport. Something I learned while producing the Lunar Poetry Podcasts series is that it’s not always wise to become so engrossed with something you’re passionate about, especially when others may be more concerned by what you can do for them professionally than who you are as a person.

When Probert became a boxing correspondent, the first boxer he had any professional dealings with was Michael Watson, then a little-known middleweight from Islington in north London. From this point on, the spectre of the horrific injuries that Watson suffered as a result of a title fight with Chris Eubank loom over the book. This, however, is the reality of boxing fandom – knowing that reading about, or watching, people who you see as entertainers and athletic inspirations are only ever one unfortunate incident away from life-changing injuries.

The book closes with Probert admitting that he has (at the time of publication in 1999) no defence for the sport, and believes it has no place in ‘civilised society’; but he also concludes that we don’t live in a civilised society. I’m in strong agreement with Ian on this point, and I feel it’s hugely hypocritical that boxing is often singled out for criticism when there are far more pressing concerns for our government.

A final point – as a writer, and a reader of a lot of writing about boxing, this quoted section from the book stood out:

To the observer, boxing appears to run the full gamut of human emotions; in its motley collection of winners, losers, liars, cheats and Samaritans, the sport presents a shrink-wrapped ready meal of the complete range of the human condition. For someone who believes they have something to say about the nature of the way in which we live our lives, boxing as a source material is worth a hundred Greek tragedies and a thousand Shakespearian epics. Perhaps the more pertinent question should be how anyone who attempts to earn a living via a keyboard could not be interested in writing about boxing.

Leave a comment