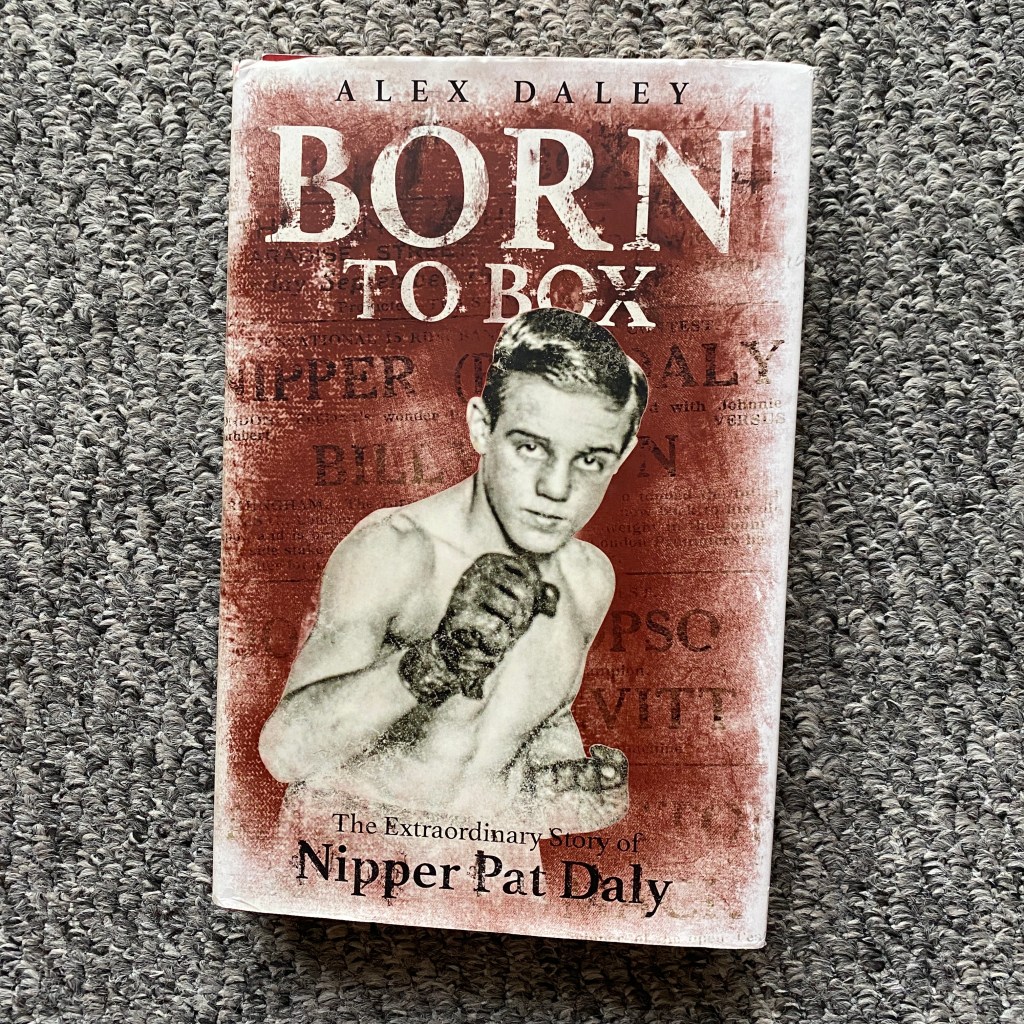

‘Born To Box’ is Alex Daley’s affectionate portrait of his grandfather, ‘Nipper’ Pat Daly, published by Pitch Publishing.

If you were to come across the life and career of ‘Nipper’ Pat Daly on the TV or in the cinema, you’d dismiss it as ludicrous and beyond farcical. Nipper made his pro boxing debut in 1923 aged 10(!), regularly fighting older and bigger opponents in a stratospheric rise to fame. This book charts his life from birth in Wales before moving to Marylebone in London, via Canada and Australia. It was while living in Marylebone that Nipper came into contact with boxing trainer ‘Professor’ Andrew Newton, aged 9. By all accounts, the boy went on to bash up everyone the ‘Prof’ put in front of him.

By the time he reached his teens, and under the tutelage of Newton, Nipper was fighting and embarrassing former and current national champions from Britain and Europe, and was spoken of as a prodigy. Almost unanimously he was expect to go on to become a world champion. Though as his manager refused to temper his workload, regardless of his young age, this praise was countered with a concern that he was being severely overworked and was in danger of ‘burning out’.

It is simply impossible to imagine anyone putting such a young child into a professional ring, or into any form of serious competitive boxing for that matter. I train regularly at Islington Boxing Club, and have gotten to know the child of one of the coaches, who coincidentally has just turned 10 years of age. He’s boxing mad, and it’s been a source of amusement at the club to watch his frustration at not being allowed to spar, or to enter his first ‘skills’ bout, while waiting to reach the England Boxing minimum age limit. To think of him being thrown into a ring with much larger and more experienced boxers is mind-boggling. Watching this young lad really highlights how different the sport was, particularly as he shares the same baby-faced innocence that Nipper has in photographs of him at the same age.

One of the great aspects of reading this book is to read about fight nights at legendary venues such as Whitechapel’s Premierland. This particular venue is mentioned in a number of books I’ve read, but this is the first which has gone into such detail when describing Nipper’s debut there on the undercard of a Teddy Baldock bill, and when he fought ‘Kid’ Pattenden there. I always enjoy reading about areas of London with a rich history of producing boxers; aside from the obvious East End, the area around Paddington where Marylebone is found comes up regularly, along with Bermondsey and St Pancras.

Throughout the book is also dotted with fantastic portraits of other boxers, trainers and promoters of the day. If you have any interest in boxing of this period you’re bound to find relevant overlaps and nuggets of information you weren’t previously aware of.

All in all this is a pretty depressing, yet necessary, cautionary tale of what can happen to any young sportsperson, especially a boxer, when the greed and ego of their guardians are put above the welfare of the child. It does however highlight how stringent current safeguarding frameworks are, in and around amateur boxing in the UK.

‘Nipper’ Pat Daley’s boxing career shot to incredible heights from the age of 10, astounding everyone who was lucky enough to witness it firsthand, before (save a couple of comebacks) it ended in retirement three weeks before his 18th birthday.

Another big takeaway from this book is, if you have elder relatives who you think you’d like to know more about, talk to them now because you don’t know how much more time you have with them. The thread of disappointment that runs through Alex Daley’s writing throughout this book, that he didn’t get to talk directly to his grandfather before his death in 1988, is clear. I share this disappointment, and regularly think about the conversations I would like to have had with my grandparents, both those I knew and those who passed before I was born. I’m sure I would never feel as though we had spoken ‘enough’, but I would at least (I hope) feel more content in the knowledge that I had listened a little more intently.

Leave a comment