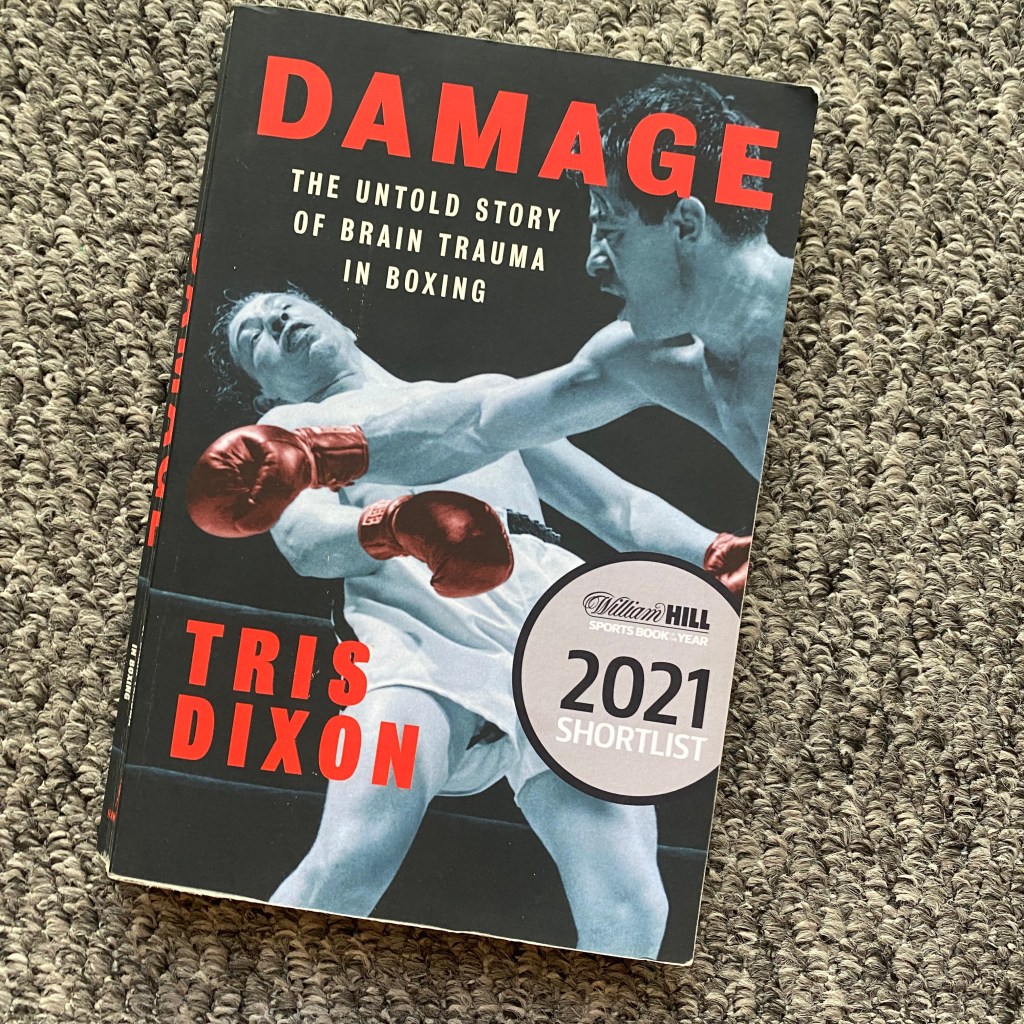

‘Damage – The Untold Story of Brain Trauma in Boxing’ is former Boxing News editor Tris Dixon’s personal investigation into the effects of the blunt force trauma that is, unfortunately, inherent in the sport of boxing.

This book focuses on Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, or CTE, also known as Dementia Pugilistica, or informally as being punch drunk. CTE is now the widely accepted scientific term for a collection of symptoms which can affect a person in a variety of combinations and over a wide timeframe, as a result of prolonged exposure to blunt force trauma to the head. It can also, though, result from single blows to the head.

This book has already had a huge amount of publicity, and rightly so. It’s a critical issue that all sports, but especially boxing, need to face up to and deal with in the present and in the future, but also retrospectively in many respects. There probably isn’t much I can add to the chat around the book as I’m not, and have never been, a competitive boxer, or involved with the media directly surrounding the sport. I am, though, an invested fan who has been struggling for a long time with the conflict of watching boxers past and present risking their physical and mental health for my entertainment.

I have loved contact sports my whole life and played rugby to a decent level, the sport that kept me out of the Chatteris ABC when most of my friends trained there as teenagers. It was also as a teenager that I began following the NFL through Channel 4’s weekend highlights programme. So, American Football and boxing… probably, for different reasons, the two sports with the highest-profile internal struggles with facing up to CTE (with rugby union not far behind), meaning that it hasn’t been very easy for me to continue following the sports over the last few years.

The NFL features prominently in this book, due to their attempts to completely cover up the evidence for CTE in former and current players, relating to the high rates of concussion, and critically, the pressure on players to continue playing while concussed. This deception resulted in a well-publicised and costly lawsuit, with the NFL paying out billions of dollars to players who had had their conditions hidden from them by their clubs.

I found it hard to follow the most recent season and I may never feel that comfortable watching games again in the future, particularly because even after this high-profile lawsuit there were still two prominent cases, with Miami Dolphins quarterback Tua Tagovailoa not being withdrawn from games when clearly unfit to play, after blows to the head – risking his short-term physical health, but his long-term mental health.

However, boxing, and especially amateur boxing, has retained its grip on me. But again, the professional game felt like a huge let-down this week, with the build-up to the Josh Taylor vs Teofimo Lopez fight descending into the verbalising of each boxer’s desire to cause permanent damage to the other, with Lopez even claiming he was looking to kill Taylor. My wife and I, though, still stayed up to watch the broadcast from New York, and in victory Lopez thankfully apologised to Taylor for his comments.

These issues around the build-up to the fight don’t of course lead directly to fighters suffering from CTE, but this form of exaggerated masculinity is a leading symptom of the culture around boxing that encourages boxers to talk of wanting to die in the ring (an issue that those around Lopez need to address immediately), rather than being pulled out by their corners; and it discourages admission of injury and concussion, in order for boxers to continue sparring and to not appear ‘weak’ around other fighters.

The book is pretty tragic at times, with accounts from current and former professional boxers about their struggles with dementia, and perhaps more tragically, from those close to boxers no longer in a position to speak for themselves. My favourite boxing character Emile Griffith eventually succumbed to the effects of dementia, and the book I’ll be blogging about next is based on Joe Grim, also known as The Human Punch Bag – both mentioned early in this book.

An issue that Dixon covers well is the fact that many former pros don’t want to go through the embarrassment of dealing with the stigma still attached to admitting that they are struggling both physically and mentally. This must be especially hard when you’ve spent your life moulding your body into as perfect a physical specimen as possible, and sharpening your ring IQ and reactions.

Secondly, many boxers feel that boxing has gifted them opportunities to live a life that simply wouldn’t have been available to them otherwise, resulting in them not wanting to bad-mouth the sport that gave them these opportunities. Likewise, when boxers have no longer been able to speak for themselves, their families have often respected these wishes and kept them hidden from the view of media and fans. This has led to many fans holding up examples such as boxer A, never had any defence and still has all his marbles, when in reality that boxer has deteriorated significantly but they are no longer seen in public.

How do we, as fans, reconcile that the punishment that boxers take in the ring for our amusement, occasionally for the glory of a championship belt, is merely the tip of the iceberg, with most of the damage being done in the amateur ranks, and in unnecessarily hard sparring; both while trying to reach their physical peak, and during the inevitable slide that most boxers face as they become opponents?

The only hope I can really have at the moment is that it is relatively rare to see a professional bout go on with a boxer taking too much punishment, before the referee stops it. In the amateur code it is very seldom that you see any boxers taking avoidable punishment, with one-sided bouts simply being stopped early to allow the losing boxer to go away, regroup and come again. As fans we do, however, end up putting a huge amount of faith in the trainers and coaches of our favourite boxers to safely and sensibly manage their sparring sessions, with appropriate rest time allowed for concussion, even if it puts high-profile bouts in jeopardy.

All I can say at this stage is that the very fact this book has been published, and not simply ignored or undermined by the entire boxing (dysfunctional) family, is a huge positive in itself. It’s a massive sign of a more generalised acceptance of the medical research around CTE, and the more anecdotal evidence. This book surely wouldn’t have been published previously. I can only say thank-you to Tris Dixon for writing this book, as he must have been acutely aware of how many people would still be upset with what they would see as a slander on boxing’s reputation.

If you’re not already aware of their work, please follow this link and consider supporting the Ringside Charitable Trust, who are aiming to set up a reliable support network to provide help to former boxers, whether that be because of financial trouble or failing health.

Leave a comment